What's that? You haven't heard of Bat Conservation International? Their mission is "conducting and supporting science-based conservation efforts around the world. Working with many partners and colleagues, these innovative programs combine research, education and direct conservation to ensure bats will be helping to maintain healthy environments and human economies far into the future." You can view their website at http://www.batcon.org/ and learn about their organization and become a member to support their cause!

White Nose Syndrome is a rapidly spreading fungus impacting migratory bat species across the United States. The goal of this blog is to track White Nose Syndrome as it progresses and focus on technologies used to identify the fungus.

Bats infected by white nose syndrome.

Monday, February 25, 2013

Bat Conservation International

What's that? You haven't heard of Bat Conservation International? Their mission is "conducting and supporting science-based conservation efforts around the world. Working with many partners and colleagues, these innovative programs combine research, education and direct conservation to ensure bats will be helping to maintain healthy environments and human economies far into the future." You can view their website at http://www.batcon.org/ and learn about their organization and become a member to support their cause!

Cumberland Gap gets added to the list

On February 10, 2013 the National Parks Service released a statement reporting the presence of White Nose Syndrome in the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park located in Virginia. Park superintendent, Mark Woods reported that histopathology tests were performed 3 deceased bats that were found in 3 of the 30 different caves found in the park. While all three bats tested positive for White Nose Syndrome, two actually showed visible signs of the fungus growing on their bodies.

As a precaution, the Cumberland Gap Park had implemented decontamination protocols within the park 3 years ago in an attempt to delay the onset of white nose syndrome. In an effort to slow the onset of WNS, visitors to the Cumberland Gap were interviewed before going on cave tours to ensure that they were not bringing items into the caves that had been in other caves or mines since 2006. Individuals were also asked to leave unnecessary items outside of the cave and decontaminate their footwear before entering caves. Researchers and employees of the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park followed current national guidance protocols for decontamination before and after their visit to the caves.

With the discovery of WNS at Cumberland Gap NHP, the disease has now been

observed in all the major mountain drainage's of the state. Virginia’s focus is now on

determining the impacts of WNS on the different cave bat species and determining if individuals

can persist over time in the face of infection. Six species of cave-dwelling bats, including the endangered Indiana bat, are found at Cumberland Gap NHP. All six species are at risk from WNS. Three species of tree-dwelling bats are also found in the park. Some bats spend both the summer and winter at Cumberland Gap. However, other bats are much more mobile, wintering at the park but spending the summer in other areas or vice-versa. Bats play a crucial role in the environment. Bats are the only major predator of night-flying insects.

As a precaution, the Cumberland Gap Park had implemented decontamination protocols within the park 3 years ago in an attempt to delay the onset of white nose syndrome. In an effort to slow the onset of WNS, visitors to the Cumberland Gap were interviewed before going on cave tours to ensure that they were not bringing items into the caves that had been in other caves or mines since 2006. Individuals were also asked to leave unnecessary items outside of the cave and decontaminate their footwear before entering caves. Researchers and employees of the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park followed current national guidance protocols for decontamination before and after their visit to the caves.

With the discovery of WNS at Cumberland Gap NHP, the disease has now been

observed in all the major mountain drainage's of the state. Virginia’s focus is now on

determining the impacts of WNS on the different cave bat species and determining if individuals

can persist over time in the face of infection. Six species of cave-dwelling bats, including the endangered Indiana bat, are found at Cumberland Gap NHP. All six species are at risk from WNS. Three species of tree-dwelling bats are also found in the park. Some bats spend both the summer and winter at Cumberland Gap. However, other bats are much more mobile, wintering at the park but spending the summer in other areas or vice-versa. Bats play a crucial role in the environment. Bats are the only major predator of night-flying insects.

Before and After

The following pictures show the before and after effect that White Nose Syndrome has on an infected Little Brown Bat.

Bats in the news as WNS spreads!

Two news articles have been released since the start of the year marking the spread of White Nose Syndrome to new locations across the United States. One article noted WNS in Mammoth Cave National Park, while the other documented WNS in the Great Smokey Mountains.

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Where did it come from?

The cause of the sudden appearance of WNS, in New York in 2006, is greatly debated. While the origin of the fungus is not known, many biologists speculate that the fungus originated in Europe. The very same fungus has been observed in Europe in healthy bat populations that have developed an immunity to the disease. It is speculated that the transfer of the fungus from Europe to North America came on the boots or clothing of humans.

Once the fungus entered populations in North America, it continued to spread because of people moving from one cave to another without properly cleaning their clothing, boots, or equipment. Samples of the fungus have been found in the soil of caves, suggesting that this transmission process is possible. It has also been discovered that bats are capable of transferring the fungus from one bat to another. A recently conducted laboratory experiment suggested that physical bat-to-bat contact is required for the spread of the disease. The same study found that bats in mesh cages adjacent to infected bats did not contract the fungus, implying that the fungus is not airborne, or at least is not spread from bat to bat through the air.

What can you do to prevent the transfer of White Nose Syndrome when visiting local caves? Researchers suggest the best measure to prevent the spread of WNS is to properly disinfect boots, equipment, and clothing after leaving a cave and to limit activity in areas where WNS is prevalent. In some areas where White Nose Syndrome is increasingly bad, caves are being closed entirely to prevent any chance of humans aiding in the transmission of fungus spores.

Once the fungus entered populations in North America, it continued to spread because of people moving from one cave to another without properly cleaning their clothing, boots, or equipment. Samples of the fungus have been found in the soil of caves, suggesting that this transmission process is possible. It has also been discovered that bats are capable of transferring the fungus from one bat to another. A recently conducted laboratory experiment suggested that physical bat-to-bat contact is required for the spread of the disease. The same study found that bats in mesh cages adjacent to infected bats did not contract the fungus, implying that the fungus is not airborne, or at least is not spread from bat to bat through the air.

What can you do to prevent the transfer of White Nose Syndrome when visiting local caves? Researchers suggest the best measure to prevent the spread of WNS is to properly disinfect boots, equipment, and clothing after leaving a cave and to limit activity in areas where WNS is prevalent. In some areas where White Nose Syndrome is increasingly bad, caves are being closed entirely to prevent any chance of humans aiding in the transmission of fungus spores.

Saturday, February 16, 2013

What is White Nose Syndrome (WNS)?

There has been a lot of talk recently about the deadly fungus, White Nose Syndrome (WNS), negatively impacting bat populations across the United States. But what is WNS?

According to the USGS, White Nose Syndrome (Geomyces destructans) is a fungus impacting bat populations across the north-eastern and central portions of the U.S. First discovered in 2006, WNS has caused the death of millions of insect eating bats across 19 states and 4 Canadian provinces. The disease infects the skin, muzzle, ears and wings of bats and appears as a white fungus.

Bats infected with WNS display abnormal behaviors such as hibernating close to the mouth of the cave they are hibernating in, flying during the day-time hours during winter, and an increased time spent out of hibernation. These occurrences contribute to the bats using up their fat reserves, causing emaciation, and a portion of the bats that die as a result of WNS. Estimates have suggested that 80% of bat populations have decreased since the on-set of White Nose Syndrome and it is suggested that populations will not rebound quickly because most hibernating species are long-lived and only reproduce one pup each year.

According to the USGS, White Nose Syndrome (Geomyces destructans) is a fungus impacting bat populations across the north-eastern and central portions of the U.S. First discovered in 2006, WNS has caused the death of millions of insect eating bats across 19 states and 4 Canadian provinces. The disease infects the skin, muzzle, ears and wings of bats and appears as a white fungus.

Bats infected with WNS display abnormal behaviors such as hibernating close to the mouth of the cave they are hibernating in, flying during the day-time hours during winter, and an increased time spent out of hibernation. These occurrences contribute to the bats using up their fat reserves, causing emaciation, and a portion of the bats that die as a result of WNS. Estimates have suggested that 80% of bat populations have decreased since the on-set of White Nose Syndrome and it is suggested that populations will not rebound quickly because most hibernating species are long-lived and only reproduce one pup each year.

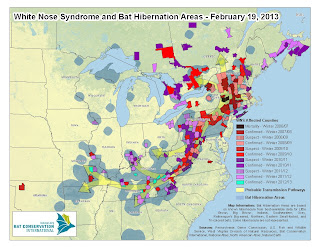

This map, provided by the USGS, indicates the presence of White Nose Syndrome across North America.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)